Part IX

Quality Control

Quality Control

MSB-23

At the inception of contract NObs-2799, there was no comprehensive military specification covering glass-reinforced plastic laminates for marine use. However, prior to the time at which process determinations for MSB-23 were complete, Mil. Spec. MIL-P-17549 was brought out and became the governing document for such fabrications. Specifications covering such materials as glass fabric, glass mat, and resins were included, and the requirements for submission of a process specification set forth. A table of mechanical properties of laminates was included which established the minimum values acceptable in production laminates. Certain details concerning laminate construction, sampling, and testing were also included in this specification.

Detail specifications for the 57 foot plastic MSB, Section C-1-b, modified applicability of Mil. Spec. MIL-P-17549 by waiving the requirement for a full scale prototype and by allowing sampling and test procedures to be varied at the direction of the Supervisor to eliminate cutting samples from structural parts.

Materials used during both the test program and actual fabrication of MSB-23 were purchased to commercial specifications, since thixotropic resins, honeycomb, and style #1044-150 cloth were not covered by military specifications then current. Glass mat, while covered by Mil. Spec. MIL-M-15617, was also purchased to commercial specifications.

Procedures covering storage and handling of materials were established as follows:

a. Glass reinforcements to be stored in a low humidity chamber prior to use.

b. Resins to be stored in the coolest available area (summer).

c. Honeycomb to be protected against moisture and mechanical damage. Cutting tolerance (thickness) to be ± 1/32".

Quality control as applied to actual fabrication of the MSB-23 was based first of all on the determination, through extensive trial and experimentation, of the most suitable materials and the best fabrication techniques applicable to the contemplated process. Material selections and techniques as developed were incorporated in the process specification submitted for the MSB-23.

Key layup personnel, as a result of experience gained during the development phases, were thoroughly familiar with the behavior of the materials with which they worked, and competent and conscientious workmanship was the keystone of practical quality control over actual laminating procedures. Naval and supervisory inspection aided in spotting and correcting errors and defects before laminates had cured, thereby keeping rejection of finished work to a minimum.

Also fundamental to successful layup operations were accurate work in handling activators and resin, and adequate mixing. Daily records were kept of all resin mixed, along with the amounts of catalyst and accelerator used in each batch. The amounts of glass cloth and mat used each day were also recorded as were room temperature and relative humidity. When observed, bulk gel time of a small sample was recorded for each batch mixed. These records gave a good check on resin-glass percentages and cumulative weight as well as a means for checking back on resin activation in the event that results were not as expected.

Actual physical properties of laminates placed in the vessel were not checked. Cutting of test pieces from the production laminate was obviously impractical and section C-1-b of the detail specifications waived this at the discretion of the Supervisor.

Tests of physical properties of #1044 cloth laminates made at the University of Michigan showed these laminates to be more than equal to all requirements for Grade E, Table I of Mil-P-17549 except for compressive strength. The lower value for compressive strength was attributed to the test method used, which did not involve the use of the restraining fixture specified in method 1021 of Federal Spec. L-P-406.

Comparative values are tabulated below:

| Property | 1044 Laminate | Mil-P-17549 |

|---|---|---|

| Flexural Strength, PSI | 26,300 | 20,000 |

| Flexural Modulus, PSI × 10⁶ | 1.55 | 1.3 |

| Tensile Strength, PSI | 25,900 | 18,000 |

| Tensile Modulus, PSI × 10⁶ | 2.95 | —— |

| Compressive Strength, PSI | 11,750 | 15,000 |

| Compressive Modulus, PSI × 10⁶ | 1.28 | —— |

Even had it been possible to cut samples from the production part, the fact that all major structural laminates were bonded to a layer of impregnated mat would have made determination of laminate physical properties through destructive testing impossible, since the mat was used only as an aid to bonding and was not intended to be included in the determination of structural laminate properties. (Laminate properties alone are covered by Mil-P-17549).

It was thought also that testing of laminates fabricated especially for test purposes would not give results indicative of properties in the main structure, since size, position, and layup difficulty would influence the final properties of the structural laminate.

Cure tests were not made on the hull layup, since the sandwich structure was never completed and the contemplated post-cure never accomplished. The partially completed hull was destroyed by fire on February 2, 1955.

ExMSB-23

After the fire and shortly before beginning work on the second boat, the contractor agreed to institute further quality control procedures as set forth in a communication from the Bureau of Ships. These procedures were concerned entirely with materials - their procurement, inspection, storage and handling, and the fabrication of quality assurance panels as a check on reproducibility of mechanical properties. Tentative specifications covering thixotropic resins and paper honeycomb had been developed, and Mil. Spec. MIL-G-11408 had been amended to include style #1044-150 cloth. These procedures and tentative specifications were included in or appended to the new process specification for ExMSB-23 and the contractor agreed to comply provided undue delay or excessive added cost did not result.

A limited amount of money was available to cover all expenses incurred in engineering, procurement, fabrication, outfitting, trials, and delivery of and for the second vessel, and any expenses incurred above this limited amount were to be met by the contractor. The contractor's cost estimates, based on few records and scant information, indicated that the funds available were barely adequate. It was for this reason that it was necessary for the contractor to agree "with reservations" to the institution of additional quality controls not required under the contract.

For the second vessel, all paper honeycomb, thixotropic resin, and glass cloth were purchased to appropriate military specifications. A sufficient quantity of previously purchased mat remained on hand to complete the boat.

For the same reasons stated in connection with the fabrication of the first vessel, laminate properties were not checked other than by close visual inspection during layup operations. Completeness of cure was checked by means of the Barcol Hardness test, the acetone test having been abandoned.

Cuttings from some secondary structural parts such as bulkheads, floors, girders, etc., are to be tested by the New York Naval Shipyard and the Battelle Memorial Institute. Results will be available for future reference.

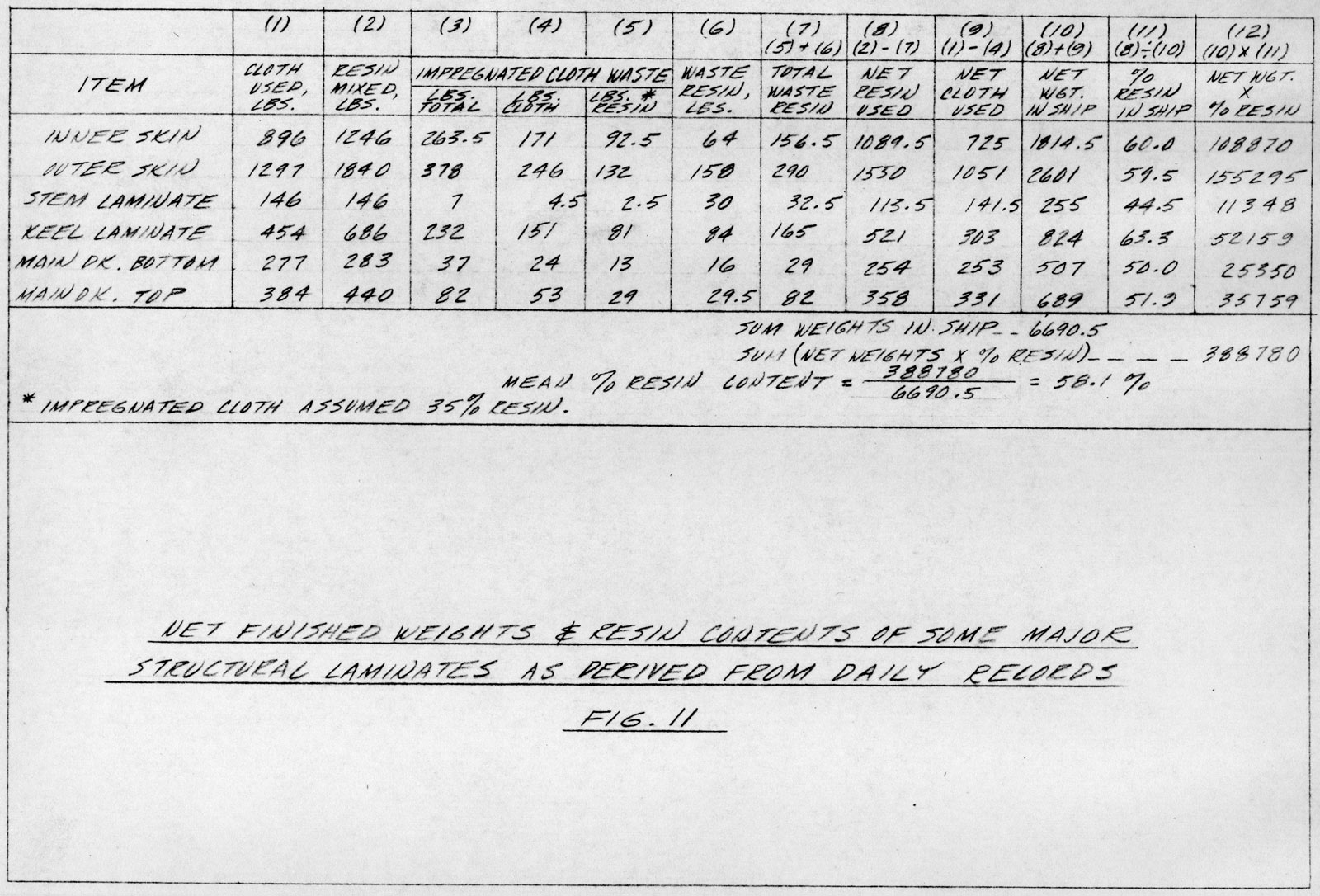

Improved forms were provided upon which detailed daily records of resin mixes and reinforcement cutting data were kept. These records made it possible to compute resin-glass percentages and allowed more detailed determination of weight distribution. Fig. 11 shows the net weight and resin content of each of the major structural laminates as derived from these daily records.

To simplify resin-activator mixing and to reduce possibility for error, charts were made up showing the amounts of catalyst and accelerator required for various batch sizes and for several reactivities. This also simplified activator adjustment to compensate for the effects of ambient temperature variations.

For several reasons, including the press of time and the appreciable extra expense involved, few quality assurance panels were made as checks on incoming materials. Those panels which were made and tested showed close correlation with early panels of similar materials (Appendix B, page 142).

The contractor was equipped to test quality assurance panels only in the form of 9" x 60" sandwich panels, so that any material under test would be subject to the performance in the panel of three other materials plus the quality of the workmanship. Thus, if a new batch of resin were being checked, the performance of the panel would be dependent not only on the resin, but also on the cloth, mat, honeycomb, and the skill of the fabricators. Considering that materials had been source inspected and certified to conform to the stringent requirements of all appropriate military specifications, it was thought that quality assurance panel tests made by the contractor would yield inconclusive results as far as specific materials were concerned.

Considering the limited practical knowledge to be gained, most of these quality assurance panels were waived on the basis of unjustified additional cost.